CryptoPunks, Bored Apes, and Doodles — these are just a few of the countless influential generative avatar projects that live within the continuously growing non-fungible token (NFT) ecosystem. Commonly referred to as PFPs, an acronym for “profile picture,” these unique NFTs have undoubtedly become frontrunners in the NFT market.

So vast is the dominance of the generative avatar sector that many people outside of the NFT space consider the entirety of the non-fungible ecosystem to be just PFPs. Yet, with a lack of understanding about Web3 and blockchain technology, most are left wondering what PFPs are and why they exist in the first place.

As generative avatar projects continue to grow in popularity, and the debate surrounding whether or not NFTs truly need utility persists, it’s time to shed some light on how PFP NFT collections came to be in the first place. Here’s what you need to know.

What is a PFP NFT?

Generative avatars, often called PFPs, are a unique facet of the NFT space. While most independent artists tend to focus on 1/1 pieces and limited edition collections, PFPs are generally conceived by groups of artists/developers and are released as a collection of thousands of individual tokens.

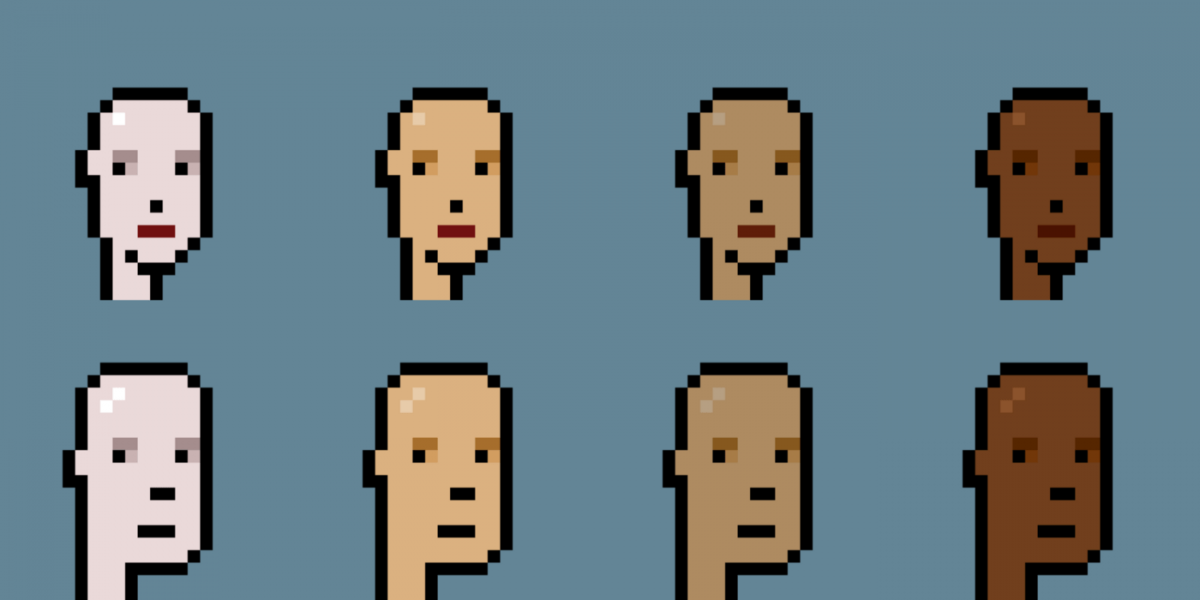

The history of PFP NFTs begins with CryptoPunks, a collection of 10,000 unique 24×24 pixel art images launched in June 2017 by product studio Larva Labs. Yet, Punks wouldn’t gain any significant traction until 2020, when NFTs first started to gain notoriety. Then, in 2021, the NFT ecosystem exploded with numerous other PFP projects, solidifying generative avatars in the NFT market.

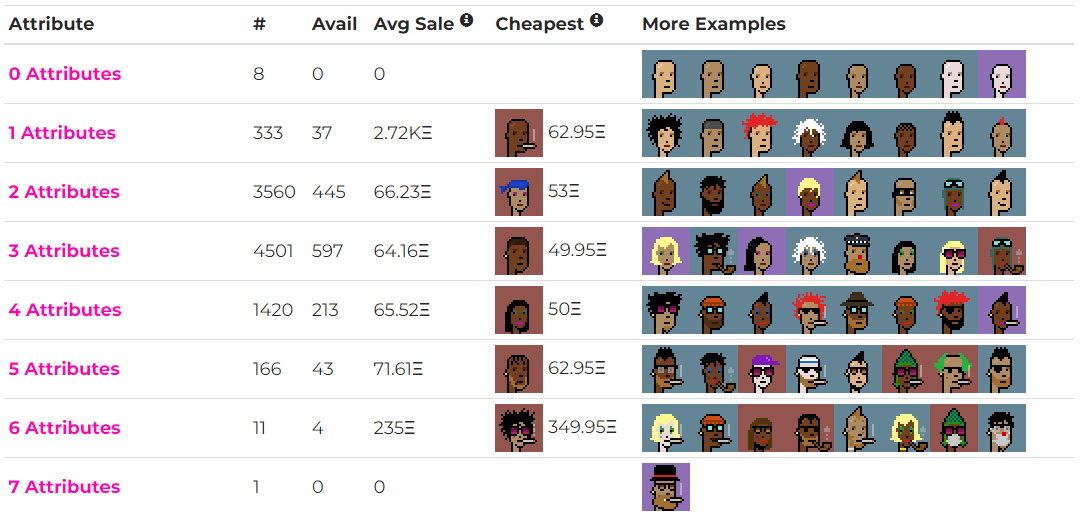

While PFPs now have their own unique existence in the NFT space, they still live at the intersection of collectibles and generative art because of how they are created. They are collectibles in that they come in large quantities (usually 10,000 or so) and have varying degrees of rarity, somewhat similar to trading cards. And they are generative in the way that (like other forms of generative art) they are created partly through the use of an autonomous system.

PFPs usually resemble, well, social media profile pictures. The subject of a PFP is often captured only from the waist, chest, or sometimes even neck up. This way, generative avatars resemble (and are easily used as) profile pictures like those you would upload to Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook.

In the NFT space, though, generative avatars have ventured beyond the usual profile-pic constraints. While many PFP collections emulate the Bored Apes chest-up style, others, like CrypToadz or Invisible Friends, have introduced full-body and even animated PFPs. Regardless of form, though, generative avatar collections are distinctive due to their vast quantities and how they are created.

So how exactly are PFP NFTs made? More often than not, PFPs are created by way of a simple plug-and-play method. Users load a variety of traits — like body type, head shape, background color, etc. — into software or an application that will, in turn, randomly compile vast quantities of NFTs, no two being the same. But these traits have to come from somewhere, which is why PFPs always start with art.

If we retrace the steps of popular projects like Bored Apes, Doodles, and Cool Cats, it’s clear that PFP endeavors always begin with an artist (or artists). In the case of the three aforementioned projects, those artists were Seneca, Burnt Toast, and Clon, respectively.

Once an artist has set their sights on a PFP endeavor or joined the cause and creative vision of a project, PFP projects become somewhat of a modular process throughout the planning and development phases.

Putting the pieces together

You’ve likely seen a statement to the effect of “all 10,000 NFTs were generated from over XXX number of traits” as part of the marketing language for many PFP projects. And all of these traits used to make PFPs are first created by an artist.

Once the project team has decided on a subject (ape, cat, duck, etc.) or an artist has settled on which of their signature characters/objects to duplicate, it’s time to figure out how to create the many thousands of NFTs that will form the collection. To do this, the project developers (devs) need to create a sort of jigsaw puzzle that can be assembled many times over via computer, i.e., the aforementioned plug-and-pay method.

Each NFT needs to be broken down into parts before it can be assembled, so the project’s lead artist must create a multitude of traits like body type, head shape, facial expression, accessories, arm position, background color, and more. For reference, check out the NFT ranking website Rarity Tools’ breakdown of all the top Bored Ape traits.

Aside from the simple creation process, artists have to consider the canvas placement of each attribute so that, once assembled, the entire composition will make sense, yielding a single cohesive NFT avatar. This means creating each NFT character in layers to ensure that ears, noses, eyes, and accessories sit right on the head of the avatar, and the head must sit right on the body, and so on.

With these layers separated, devs can load each trait into a program (like Python) or write some code that can mix and match the attributes to create single NFTs quickly. The programs vary depending on the team and whether they hope to generate each avatar beforehand or in real-time during the minting process.

More often than not, though, after a few generative trial runs to work out any potential errors, devs will generate the total supply of 10,000 or so unique, non-duplicated (but sometimes very similar) NFTs. Creating a 10,000 supply PFP project has become incredibly easy thanks to this plug-and-play method.

It’s important to note that not all PFP projects require a generative aspect. While generative avatars and PFPs often go hand in hand, at times, independent artists will take on a PFP project, illustrating or crafting batches of hundreds of NFTs in their style. One such example of this is Ghxsts — a project consisting of over 700 NFTs that were each drawn by hand as 1/1s but altogether seemingly fit the definition of a PFP collection.

Releasing PFPs onto the blockchain

The final step in the PFP process is the most public and likely best understood in the project pipeline: releasing these new PFP NFTs into the world.

Yet, this final step is entirely dependent on whether or not NFTs will be generated during mint or pre-generated offline and loaded into a sort of randomized, first-come-first-serve grab bag. For independent artists, like Jen Stark and her Cosmic Cuties, generating offline then loading the entire supply onto a marketplace like OpenSea and selling them over time usually makes the most sense.

In the case of large-supply projects, though, many other steps must be completed before PFPs go up for sale. Before release, devs focus on creating a website, setting up a smart contract, testing the minting functions of both the website and the smart contract, deciding on a sale method, setting a release date, price, and more.

This is because, above all else, the release of a project is quite possibly the most important event of all. For a high-level summary of the technical side of releasing a PFP collection, read security researcher Harry Denley’s post here.

Smart contracts and file hosting/sharing aside, this final step mostly comes down to whether or not the project team can generate hype, cultivate a following, and deliver a solid product to their potential collectors. We’ve seen collections time and time again (Mekaverse, Pixelmon, etc.) create obscene amounts of hype only to fall short of their potential — with others, seemingly too good to be true, succeeding beyond expectations.

The public sale has a lot to do with the overall perception of the project. Of course, whether or not the generative NFTs look good plays into things, but rollout mechanics, including whitelisting and pre-sales, Dutch auctions vs. releasing in waves, etc., all play a massive role in how a project is perceived.

Suppose this all goes smoothly and the collection sells out quickly. In that case, collectors are likely to be much more pleased with the process and the product — as opposed to when projects like Akutars charge full speed into a sale and hit significant and debilitating roadblocks.

But why would someone want to buy a PFP NFT in the first place? Well, aside from the potential of a generative avatar to increase in value, minting a PFP NFT often comes with perks, including membership into an exclusive holders-only Discord server, access to live and virtual events, first dibs on subsequent collections, and of course, bragging rights and the ability to change your social media profile pic to the unique new NFT you own.

The top PFP projects of all time

Considering the overwhelming success of Bored Apes and CryptoPunks, it’s no surprise that NFT enthusiasts of all types are so gung ho on PFPs, or that dev and artist teams everywhere have attempted to follow in their successes. Yet, while most derivative collections have come and gone, it seems that while the NFT market is saturated with PFP collections, originality still prevails.

This is precisely why many PFP collections continue to stand the test of time. Below you’ll find a list of some of the most influential generative avatar collections to grace the blockchain. While there are hundreds of projects out there, these few are among the one percent that continue to make waves (for various reasons) throughout the NFT ecosystem.

CryptoPunks

As previously mentioned, Punks were launched in June of 2017 by Larva Labs, which Yuga Labs acquired in 2022. These Punks were some of the first NFTs ever minted on the Ethereum blockchain, making their importance immeasurable in the grand scheme of NFT history. Featuring humans, apes, zombies, and aliens, CryptoPunks pioneered the idea of generative trait combinations that most other PFP projects still draw inspiration from today.

Bored Ape Yacht Club

Second only to CryptoPunks in importance, but undoubtedly first in popularity and value, is the Bored Ape Yacht Club. Also, a collection of 10,000 NFTs, BAYC, launched in April 2021. Although it experienced a slow start, the project exploded in value over the following months, becoming one of, if not the most beloved NFT project of all time.

Doodles

Doodles, which also consists of 10,000 avatars, launched in October 2021 and has easily become one of the most popular PFP projects in all of NFTs. Featuring a vibrant community, seasoned executive team, and a multifaceted approach to entertainment, Doodles has yet to cease winning over the hearts of countless NFT enthusiasts and veteran NFT collectors.

Moonbirds

Moonbirds, another collection of 10,000 NFTs, was created by prominent American internet entrepreneur Kevin Rose as part of his Proof Collective — a private members-only collective of NFT collectors and artists. Only a few days after its April 2022 launch, Moonbirds had already achieved upwards of 100,000 ETH (approximately $300 million at the time) in secondary sales volume, immediately making it one of the highest-grossing NFT collections of all time.

Cool Cats

When it comes to community-driven projects, Cool Cats is a tough one to beat. A collection of 9,999 generated and, as the developers say, “stylistically curated” NFTs, the collection launched in June 2021, earning accolades and being propelled by collaborations with Ghxsts and TIME magazine, plus a near viral milk chug challenge.

These are only a few of the dozens of generative avatar projects that dominate the NFT market charts. Read about more interesting and influential PFP NFT projects here.