Hello,

Over the past year, I have been hearing from multiple founders that fundraising has gotten more difficult. (I wonder why). Being on the venture side for most of the last two years, I find it hard to gauge the sentiment objectively, so I ran a poll (n = 101) to get to the bottom.

While my polling method was certainly a bit crude, the consensus is clear: The year has been terrible for seed-stage financing. It would make sense if you considered how much longer it takes to close a round. Venture investment activity typically correlates strongly to major stock indices, and we are in a bear market. Hence, it should be a terrible time to be a founder raising money. Or so the logic goes.

I looked at about six years’ worth of data to see if that’s true. This piece explores how the current blockchain fundraising environment of 2023 compares to the bear market of 2018 and lays a framework for what founders need to know to survive this year.

Note: You can read my previous reports from 2021, 2020 and 2019. I did crunch the numbers in 2022, but we were in the middle of a raging bull market, and I had other priorities at the time.

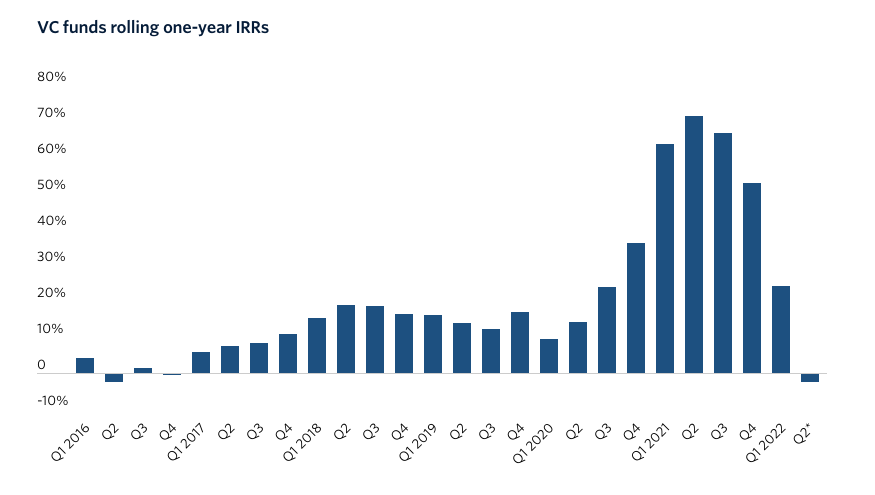

Before diving into the challenges Web3 faces via insolvent exchanges and dysfunctional stablecoins, let’s first shed light on the state of venture capital itself. We are in this odd phase where the venture market’s internal rate of return has flipped negative for the first time in six years. The metric is an average across funds, so it is safe to say venture as an asset class is in murky waters from the lens of those putting money into it. These are generally institutions like pension funds or funds of funds.

Looking at digital assets in an isolated sea of venture returns alone doesn’t make sense. Some funds actively trade these liquid instruments. I was curious to see what the state of hedge funds is like, and they don’t seem to be doing too well either. By some estimates, hedge funds are about to survive their worst year since 2008. And crypto-related hedge funds are down 55% on average on their AUM.

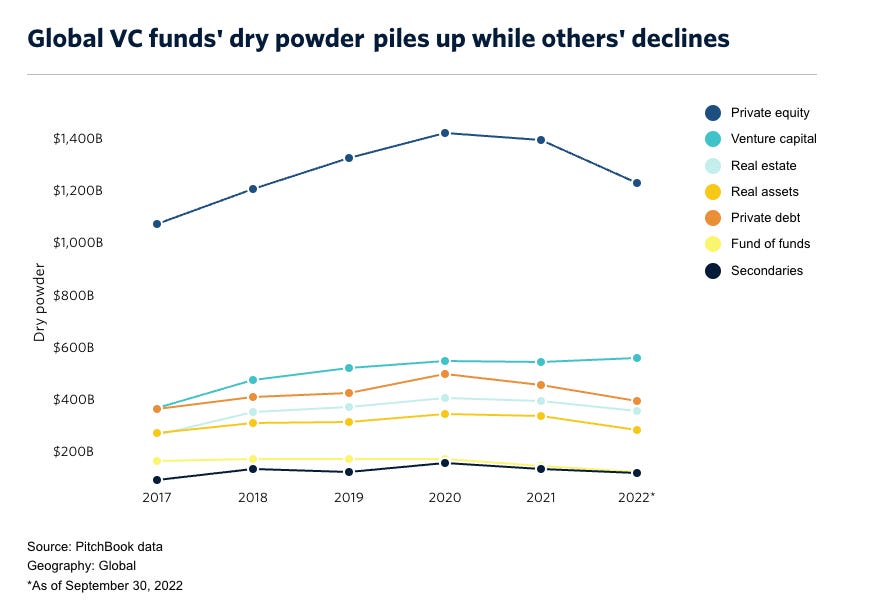

Theoretically, this should lead to startups seeing lower amounts of funding. Right? That’s the assumption I went with when I started this piece. But consider the chart below.

In terms of total capital deployed, we just had our second-best year. There is a decline of ~20% in money being deployed YoY, but it is still lower than the ~35% reduction the broader venture market has seen.

Does that mean venture funding in crypto is intact?

Most likely not. Much of the funding that was seen in 2022 happened in January when founders and investors returned from their winter vacations and kicked off the new year by announcing their raise. That’s why you can see a seasonal uptick in amounts raised and frequency of deals during that month. Over the year, we witnessed firms with moderate amounts of traction going for large raises to have a runway, while Do Kwon, Su Zhu, and Sam decided to set fire to the industry.

This trend becomes more obvious once you look into the number of deals that happened that year. I zoom in to the last year to show what may have happened.

Notice that “crash” around February? That is VC fund associates and analysts catching their breath after the uptick in January. You can see it in 2021 numbers too.

But here’s the crux of the data:

We have reverted to frequencies of venture funding last seen around Jan 2020.

That reversion to the mean is visible in terms of capital as well. Considering the macroeconomic pullback of Q1/22 (rising energy prices, possible inflation), we saw a rapid decline in the price of digital assets. Typically, investment appetite tends to reach new highs when liquid markets perform well; it indicates that a Web3 investor could see an exit in the form of a liquid token.

As markets deteriorated, firms began increasingly delaying their token releases. Because nobody wants to release a token into a crashing market. This meant existing positions held by investors would take longer to produce a return.

In such circumstances, the rational response is to hold on to dollars that are not yet deployed instead of pursuing hot rounds. This becomes quite apparent when we look at the amount of money deployed.

The chart above summarises the wave of venture dollars that entered the ecosystem in late 2021 and slowly receded over the year. What I find fascinating is that even at that “low” $650 million a month, the blockchain ecosystem today attracts, each month, what the industry received in funding in all of 2016.

Granted, the number of firms in the crypto space has risen exponentially, and it is wrong to suggest we are in a huge funding freeze without considering how the space has evolved in fundraising activity over the last few years.

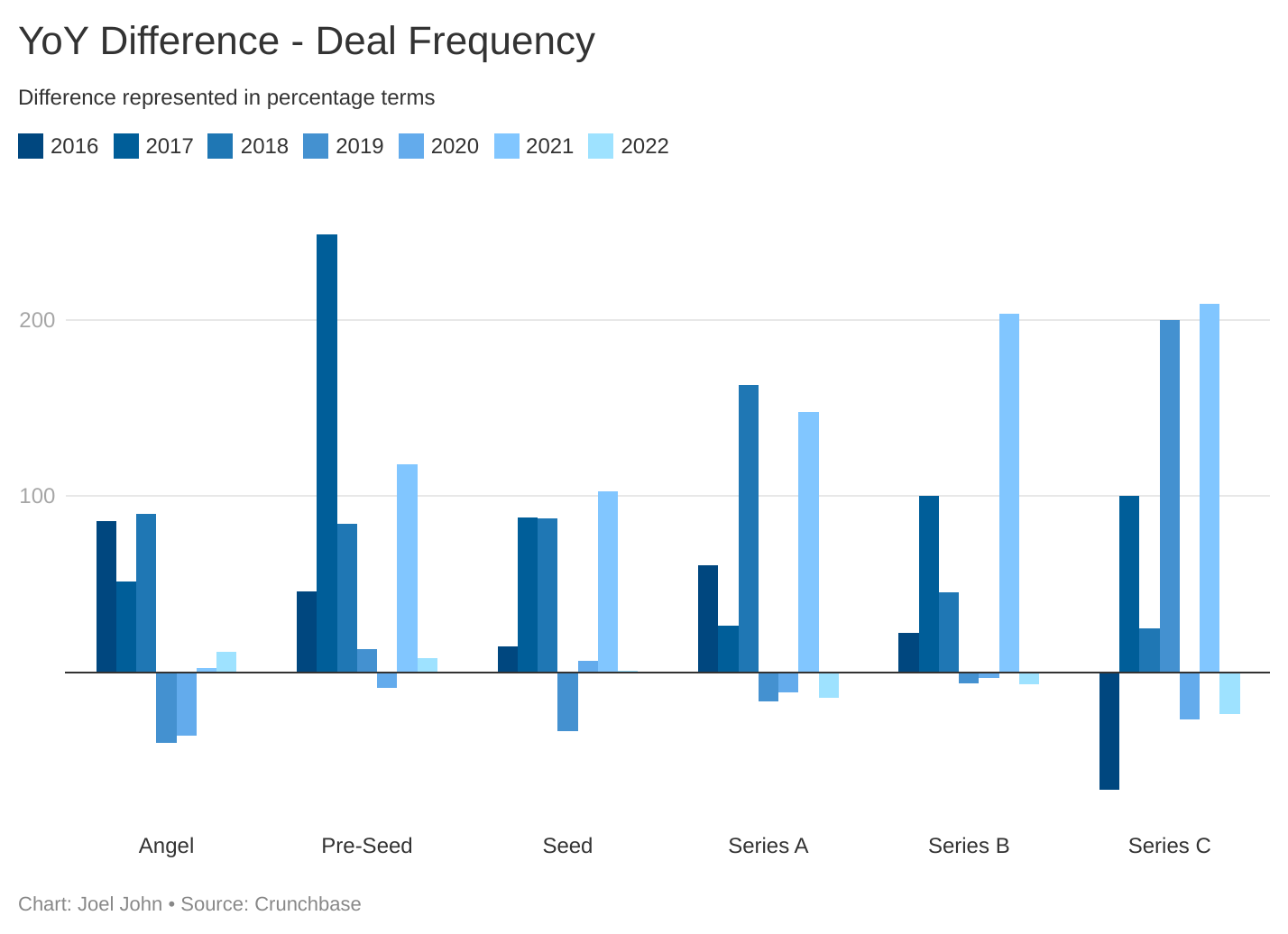

To do this, I crunched numbers that go way back to 2017. If we are in decline as bad as the winter crash of 2018, we should see draw-downs in frequency that sync with what we witnessed then.

We see two separate trends when we consider deal frequency over the years. Firstly, the pre-seed and seed stages remain more resilient than in 2019. In 2019, there was a ~33% reduction in the frequency of seed stage raises. YoY, we managed to stay in positive territory for 2022. Founders have been raising more at seed stages to build through a bear market. The median amount raised at seed stages has risen over four times since 2020. It is at $4.5 million per raise now.

You will see an entirely different trend if you look towards the right of the chart at Series A, B, and C.Series A was at -17% for 2019. We are at -15% for 2022. Series B and C have similarly begun imitating their 2019 peers. Founders can close rounds between friends, families, and angels in the early stages. Seed stage raises have gone from taking a few days during the bull market to over two quarters in the current environment.

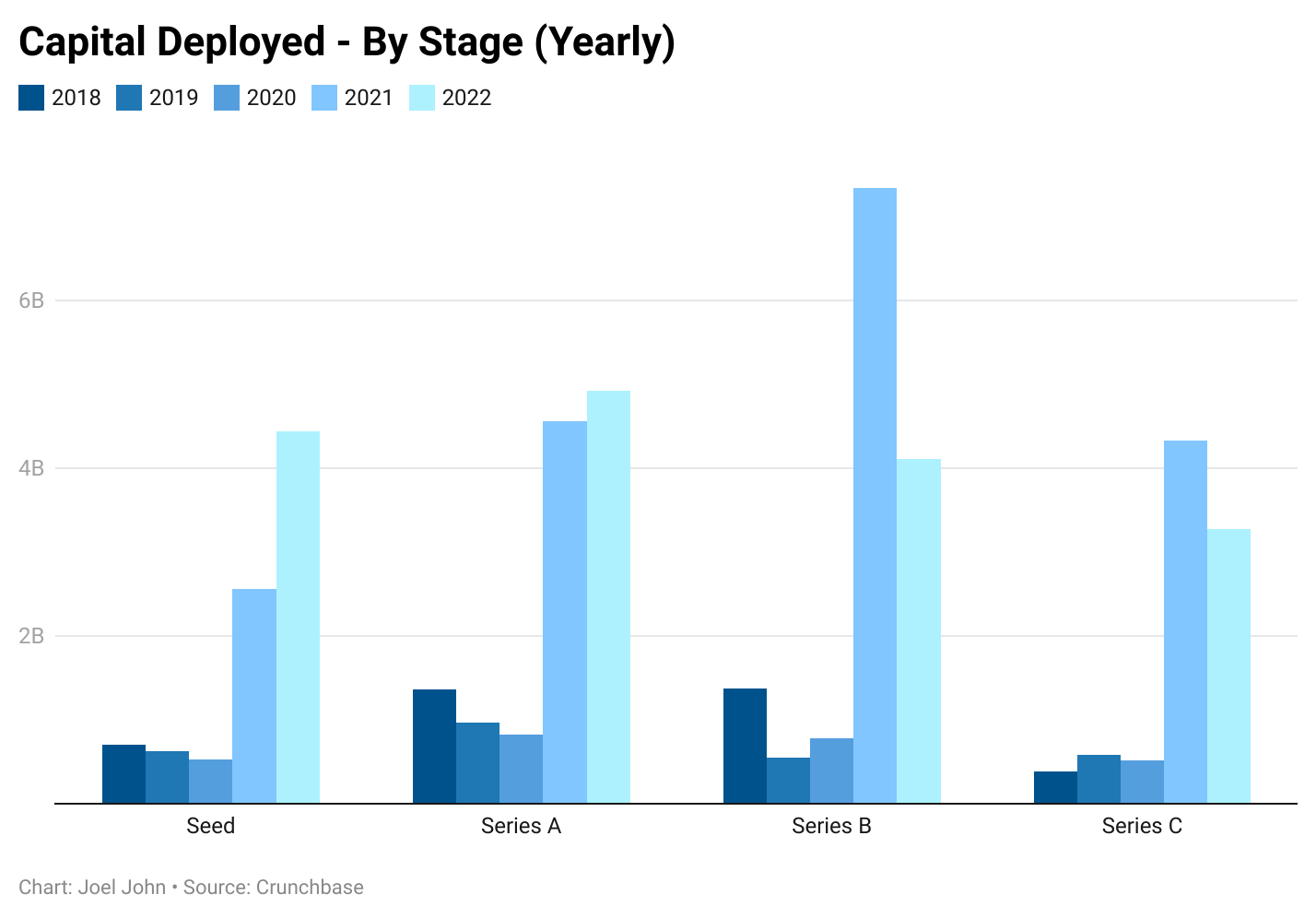

But they still happen. For growth-stage firms, the possibility of a raise is next to impossible unless they have traction to show. This becomes quite evident if you study the same figures through the lens of capital deployed YoY.

The amount of money that has gone into seed stages has doubled. While Series A has stayed at the same pace, we see a serious contraction only at the growth stages. This may occur because firms try to stay lean early, and a large enough raise could mean they stay around long enough to enter a bull market.

At later stages, firms have generally raised a lot of capital and hired a significant headcount. With high burn rates, the probability of surviving 36 to 48 months for a change in market sentiments is relatively lower.

If you are a growth-stage investor looking at a steep decline in the valuation of bets you have already placed, you generally have two options. The first is to go towards earlier stages (seed, Series A) and join in earlier rounds. It explains why we see firms that historically only participated at late stages joining in early rounds these days. From the portfolio construction perspective, it averages down the valuation you have deployed and increases your stake in different firms.

A second option is to bet big on ventures already doing well. This is why firms with traction generally have monster raises.

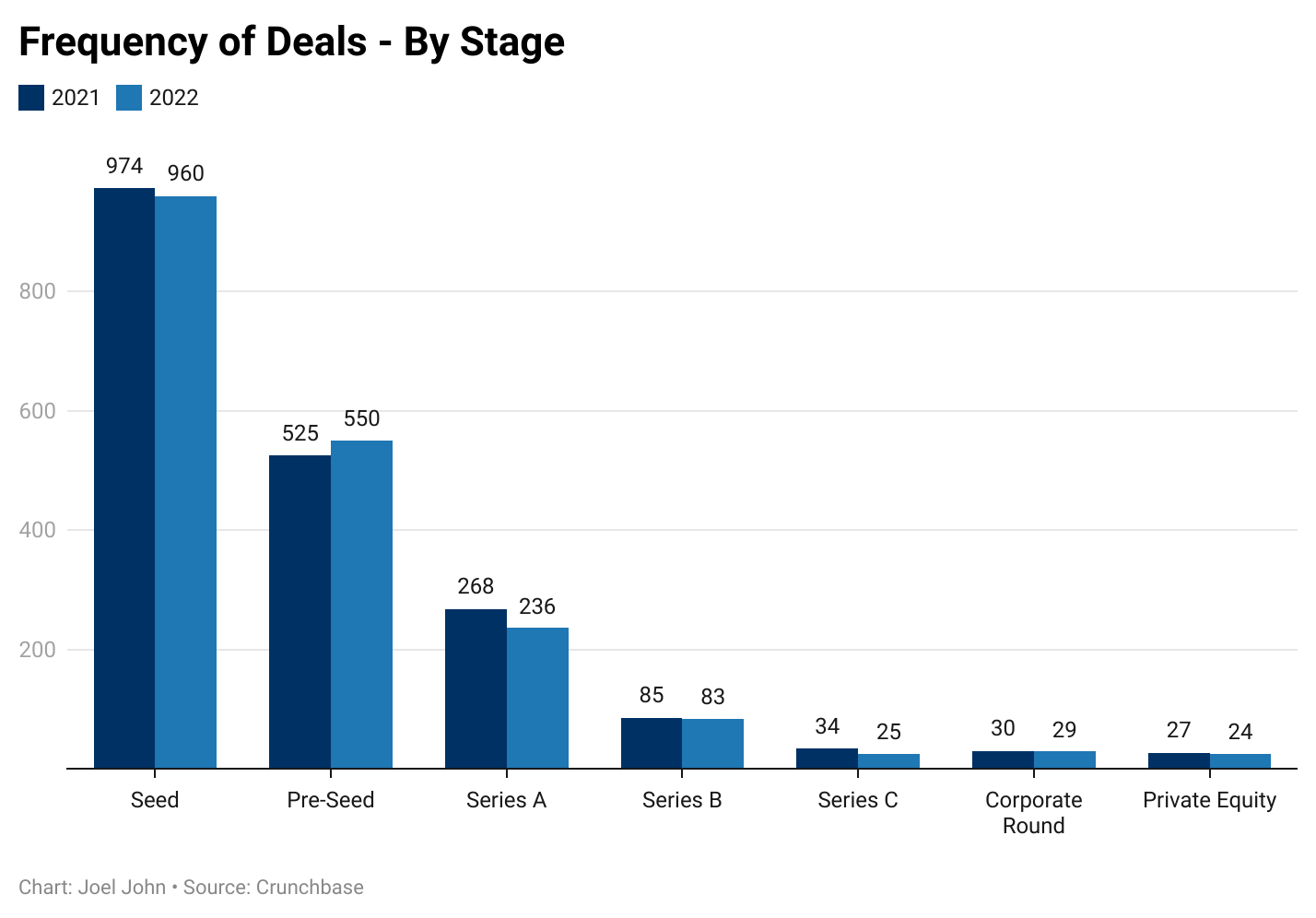

What does all of this mean for founders in today’s market? It is worth remembering that – contrary to public opinion – more capital and deals are happening in crypto now than in 2020. The chart below breaks down deal frequency by stage over the last two years.

Your fear is slightly unwarranted if you are at seed or pre-seed levels. There are just as many deals happening and twice as much capital entering the ecosystem.

It serves the interests of those deploying money to convince those raising money (i.e., you) that the sky is falling. It allows them to push for more favourable valuations while giving them ample time to consider other ventures they can deploy into. There is no coordinated conspiracy to have founders believe that venture funding is coming to a freeze. Instead, it is the market’s invisible hand, as Adam Smith would have worded it. A flurry of forces that work in tandem to have you believe there are no more buyers in the market.

This is how it works. During a bear market, venture investors with dollars to deploy have the optionality of sitting out till the “perfect” opportunity comes along. The proverbial pendulum of the market swings in their direction. Every firm takes longer to do its due diligence and return to its founders.

What would have taken a few days in a bull market often takes months during a bear market. Partners at large firms start the conversation with traction metrics as opposed to who else is joining the round. Founders translate this apathy from venture backers as a lack of capital in the market. It is not the absence of money that causes this behaviour. It is the lack of conviction.

But there’s a different cause to the madness. We think a startup failing to raise follow-on funding is the worst thing in the world. We believe that failure is not an acceptable outcome in a market where the cost of failure has shrunk to zero in 2023.

Until the 1990s, it was rare to see entrepreneurship as a viable career path for young professionals. You had to either take on debt or be born into a rich family. Venture capital flipped this dynamic during the dot-com boom.

What is now occurring has been best explained by Ramana Nanda, a visiting scholar at Harvard. Titled “Cost of Experimentation and the Evolution of Venture Capital” it explores how the declining cost of starting a venture has affected the quality of founders and the investment style of their backers:

“The falling cost of starting new businesses allowed a set of entrepreneurs who would not have been financed in the past to receive early-stage financing. While these marginal ventures that just became viable had lower expected value, they seemed to be largely comprised of ventures with a lower probability of success but a high return if successful (what we refer to as “long shot bets”) rather than just ‘worse’ ventures with a lower gross return when successful. We find that in sectors impacted by the technological shock, VCs increased their investments in startups run by younger, less experienced founding teams.

While these characteristics are consistent with anecdotal accounts of “long shot bets” such as Google, Facebook, Airbnb and Dropbox being founded by young, inexperienced founders it is of course also consistent more broadly with alternative mechanisms that would point to the marginal firm just being a worse investment.”

Nanda wrote this in 2015, nearly a decade after Amazon Web Services (AWS) launched. Why does that matter? Because the likes of AWS and Google Ads changed the unit economics of entrepreneurship. They allowed anybody to spin up a server and sell to someone halfway around the globe.

For instance, Y Combinator relied on an ever-increasing number of young people that often knew no better than to go out and make the primitives we use every day on the internet today. Surely the failure rate across these ventures was – and still is – quite high. But taken together, the world is better off with these startups funded than without.

Crypto has similarly collapsed the cost of entrepreneurship a decade later. Where AWS focused on the cost of servers, primitives like DAOs, NFTs, and DeFi have collapsed the cost of capital coordination. This means we will have even younger people conducting financial experiments more frequently and on a global scale. And a lot of them will fail. The system is designed with the understanding that they will.

Pundits often rush to suggest the industry is collapsing because we see failure at a high frequency. But the market is simply following what has been a multi-decade-long evolution. A consistent rise in the frequency of early-stage financing of (seemingly) young founders, justified by outsized returns by a handful of firms.

This is power law on steroids. Our operating assumption is that all startups will make it. WAGMI sounds good on Twitter, but reality operates with a different agenda.

Venture capital is one of the only private instruments that have seen an uptick in inbound volume over 2022. Depending on the source, $300 billion to $600 billion in cumulative capital has not been deployed. A huge portion of the capital is only “committed,” and the institutions VCs have raised from can potentially back out, if we have a full-blown recession like 2008. There are precedents for this in 2008 and the dot-com bubble.

The operating assumption for many founders has been that VCs will, at some point, have to continue deploying money. And that is indeed true. But if data teaches us anything, it is these two things:

-

VC at the early stages occurs at high frequency, with ever-increasing sums of money. A large portion of these startups will likely fail. Failing quickly is a desirable outcome as it saves time and energy for everyone involved. VCs generally set valuations to optimise for ownership if one of these startups takes off.

-

There is excessive capital piling on firms at growth stages that can show meaningful traction. These are firms that will raise at a premium compared to their peers. It is a seller’s market. Founders get the valuation they ask for as there is too much money chasing too few deals.

The messy middle is what most founders want to avoid. This area is where you have raised enough capital to grab headlines and the best people but have no clear direction towards achieving product-market fit. The worst thing to happen to a venture is not shutting down. It is apathy – from your customers, team, and investors. A slow bleed, marked by a thousand cuts that reminds you nobody cares about what you pour your heart and soul into.

This “messy middle” I refer to generally pops up right around Series A. Because that’s where you have “validated” the venture externally through VCs or media firms – but not through paying customers. This is why conversations around fundraisers at these stages start with identifying key metrics of the venture. If the numbers aren’t there, the follow-on dollars won’t be coming anytime soon.

I don’t mean to fearmonger here. But it is worth acknowledging that there will be failures along the way. DAOs no longer deploy money like they used to. Ecosystem grants, a lifeblood of the industry, have reduced deploying money. And angel investors who saw their wealth from IPOs and tokens listing at high valuations are scrambling for jobs amidst tech layoffs.

Will there be only good days in the months that follow? Likely not.

Especially if the macroeconomic environment stays the way it is. But things are not as ugly as we perceive in private markets. Seed stage activity is still as high. Late-stage deals are raising just as much. If you are building and you have the numbers to validate your assumptions, there is not much to worry about.

I’ll see you guys next with some work we have been doing around NFTs and their royalties.

Joel John.

Ps – We are close to releasing a venture dashboard that tracks all investment activity in real-time. Drop me a text on Telegram if you’d like to beta-test it.

Before these pieces go live, I discuss most things covered in the newsletter on our Telegram. It is where we stay updated on all things Web3 and discuss what could be next in the market. Consider joining us to connect with ~2500+ researchers, investors and operators.