Hey there,

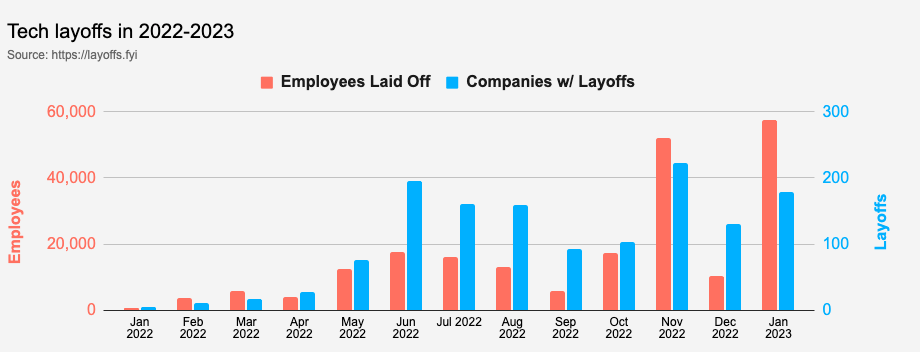

It has been a scary few weeks for anybody working in the tech sector. Layoffs are at an all-time high, and the pundits are out in full force, reminding anybody that would listen that the past decade is not indicative of how markets generally work. Startups went on a hiring spree to keep up with demands for growth during a period of low inflation. Now that the Federal Reserve is back to raising rates, we are quickly reversing to reality. An ugly one while at it.

All of this made me think of the value of labour in the digital asset ecosystem today. Surely, a huge part of the equation for the industry is financial capital. We require money to flow through our DeFi and NFT products. But amidst the speculatory hubris, we miss out on a different part of the equation that could strengthen the ecosystem’s GDP. That is labour.

Technology becomes relevant when it enables economies to grow. Or else it dies. Shipping or rail networks empowered the quick transportation of goods, bringing markets closer. Communication networks like Telephone or Telegram enabled faster communication between potential buyers and sellers. The arrival of electricity and light bulbs meant factories could now be open through the night, bringing in the concept of “night shifts”.

More recently, the internet made global-scale collaboration a possibility. We argue about things like remote work or living the life of digital nomads because an emergent technology (the internet) enabled it.

At stages of infancy, all technologies are instruments of novelty. It takes time for it to be a tool for productivity at a massive scale. Digital assets serve the purpose of novelty quite well today. If you believe your life is devoid of comedy (or tragedy), consider spending half of your net worth buying dog-sounding tokens. And see how your life changes. It’s a different story when you ask what percentage of the industry is doing work that is additive to the overall economy. Or, put differently – what portion of the wealth in the digital asset space comes from doing work instead of putting in capital to buy tokens?

In its present form, the internet is an arbitrage machine for labour. Corporations are incentivised to hire from remote regions as they can benefit from the lower salaries required in much of the emerging world. In instances where pay grades are at parity with what is paid in developed economies, employees are incentivised to move to regions with lower living costs to save faster. But if the markets are efficient, this arbitrage may not last forever, especially for highly skilled knowledge workers.

Take any niche, highly skilled job, and you will see that the supply of workers who can perform it is limited. As the demand for these employees increases, pay scales will likely match what they would be at a global hub like Silicon Valley—essentially eradicating any possibility of continuing said arbitrage in terms of wages. Founders paid solidity developers FANG-level salaries in the last bull cycle.

When time is of the essence, and the labour supply is limited, markets rapidly reprice what they are willing to offer talent. Regardless of where they work. You could be in a condo in New York or working out of a basement in Bangalore; the pay eventually has to come to parity, assuming the output from both employees is of similar quality.

I was thinking of this to understand why people join the blockchain ecosystem in emerging markets like India. Early on, users came for ideological reasons. However, part of the crowd also joined in for alternative means of wealth creation. ICOs, NFTs and DeFi compressed the risk the average person took in a lifetime to a matter of months. And in some instances, it also made them the wealth they would have made in a lifetime. (Albeit, in a few cases, it involved securities fraud).

But what reasons do people joining the ecosystem today have for working at a Web3 native firm? What would make a person wilfully think “I am comfortable working with a group of dudes texting each other all day on Telegram, pretending that governance happens with tokens”? Of course, profit motives are a massive part of the equation. Everything from play to earning to working for a DAO is appealing in emerging markets because the pay scales are generally at a premium to what a local alternative can offer.

A different way to think of it is that individuals are more comfortable working remotely, detached from their peers and without the serendipity that generally comes from working at an office because the trade-offs make sense to them. The premium they earn in their wages justifies what they miss out on by doing conventional jobs.

But there are also more personal motives. Some people value the optionality of working with brilliant people online whilst being able to log off and be with their ageing parents. For others, it could be the opportunity to work on an emergent technology without dealing with the bureaucracy (and injustices) that come through an immigration department.

But how many people even work in the ecosystem today? Going by a very crude (and likely wrong) measure, if we assume 10% of all DAO voters in the last six months were employed by DAOs in some form, we are at a mere 6000 individuals. Data from Nansen suggests some ±60,000 voters have voted on different proposals this year. That is a small, abysmal figure. And every DAO-tech firm is practically trying to get a portion of that userbase.

Add to this the number of people employed through centralised Web3-related firms. If I take a generous figure of ±300,000 people employed by exchanges and half as much by smaller start-ups, we will come to ±450,000. Less than 1% of the ±62 million people who are employed full-time in technology-related businesses today are in Web3. The actual figure is likely a quarter of what I have stated. So neither DAOs nor centralised blockchain-related ventures onboard people to the digital asset economy today. But there may be a market section that has done it at scale: NFTs and Gaming.

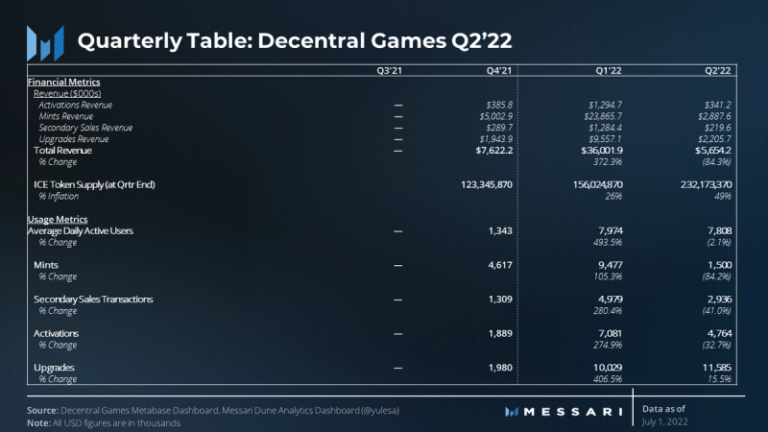

Play to earn as a concept may have died a miserable death over the past year. Between collapsing token prices and poorly designed token economics, the incentives for gamers that grind to make a living became non-existent. But it was perhaps the first time we saw large groups of people doing “labour” in digital-first economies.

For a brief, short-lived period, tens of thousands of individuals made an income defying everything we knew about work up to that point. P2E economies demonstrated that global-scale, digital-first workplaces designed around leisurely activities could become a reality.

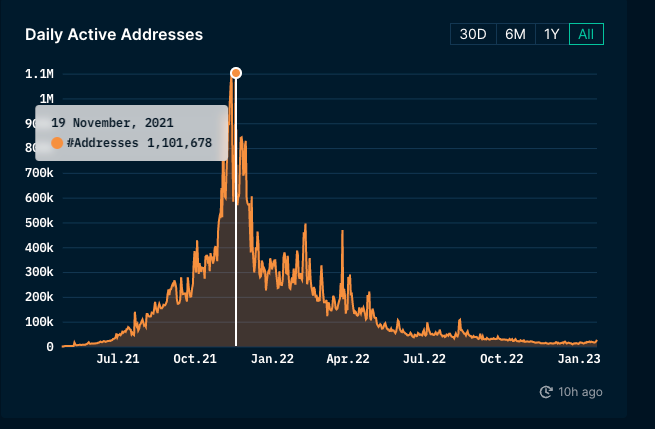

This could occur because blockchains made it possible to create low-value, high-frequency transactions worldwide. Axie Infinity’s users often did not have access to complex financial infrastructure. But they could be paid in a matter of minutes when they were being paid through guilds or the game’s native token (SLP). At one point, founders built startups to enable users to pay their bills in the Philippines using the native token. In addition, ad listings for houses often mentioned that it would be acceptable to make the payment for a property using in-game currency.

If I take the count of active wallets engaging with SLP (at peak) as a proxy for the number of users Axie had, it will come close to a million. Not bad. But not everybody wants to grind out in games to make a living. That is why creating infrastructure that empowers individuals matters. One of the few ventures that have done this at scale is OpenSea. As of November 2022, close to a billion dollars were paid out through the platform in royalty fees for the year. 80% of that figure went to creators that were not in the top ten.

These two data points indicate a more significant trend. At its crux, it’s unlikely “crypto” as it stands today will employ much larger groups of people. We may not have a few more million people working full-time in the industry. What may happen instead is that the infrastructure we build will do one of two things.

On one side, they will create new jobs that did not exist in the past. And on the other, they will embed into existing jobs and expedite processes around payments and identity verification. There is precedent for this if you study how the internet evolved.

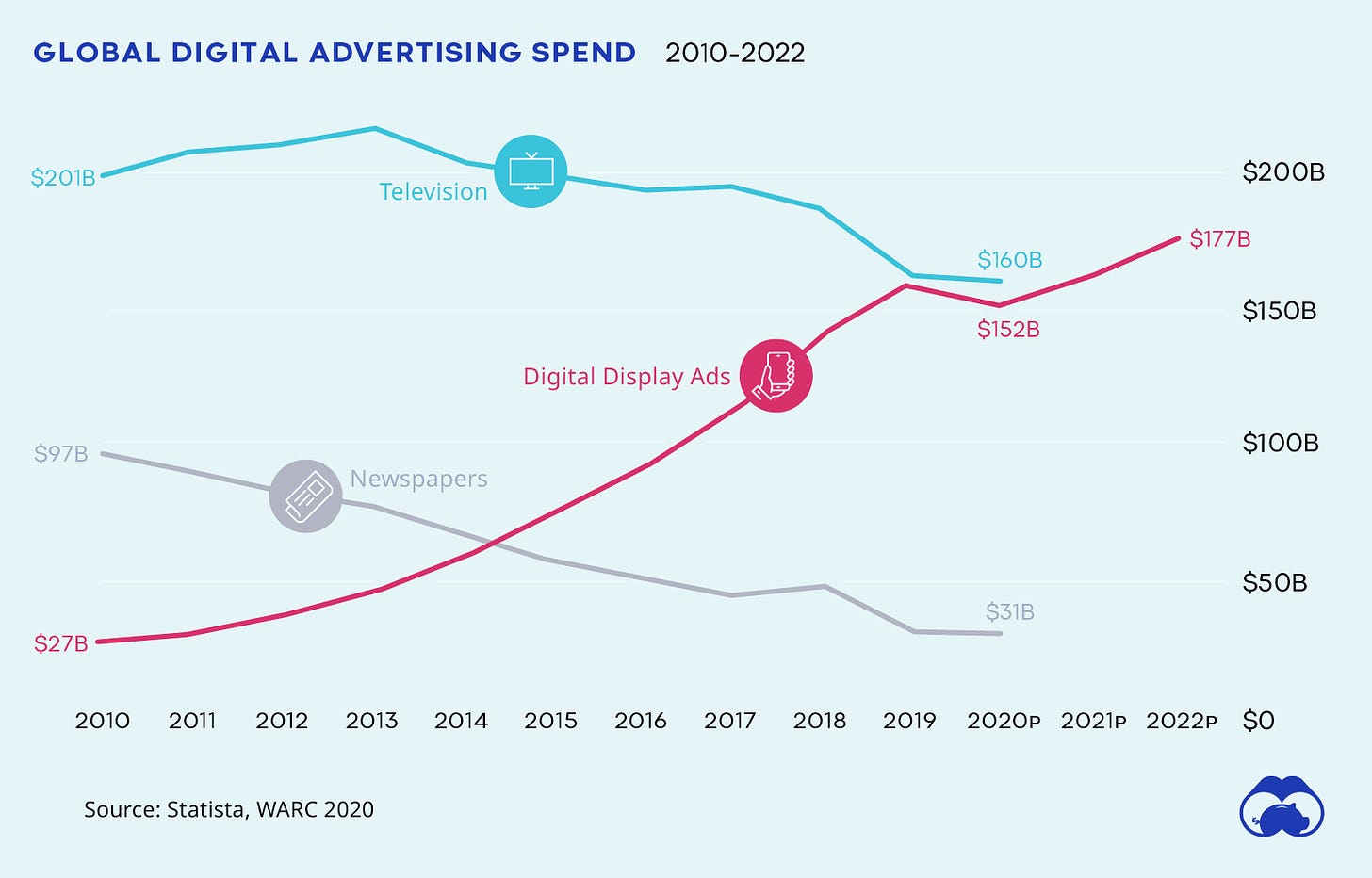

In the early 2000s, it may have seemed absurd to think one could do a job out of posting content on social media networks. The creator economy was a distant concept. And yet, in 2022, becoming an influencer is a leading “aspirational job” when kids are asked about what they want to be when they grow up. For this to occur, there were two forces at play.

First, sufficient eyeballs transitioned from consuming media via cable or the newspapers to digital-first social networks like YouTube or Instagram. And secondly, a generation that started sharing every small tidbit of their life grew old enough to be working adults. We are seeing a variation of this with NFTs today.

The kid grinding it to secure a whitelist spot on a new NFT release will be the executive that determines how a brand markets itself in a decade. As a younger population that has used and understood the basics of these primitives becomes decision-makers, we will see it becoming the norm for employment around these instruments surging.

Jobs will have to be structured around the design, distribution and economics of digitally scarce primitives and our universities are far from equipped to enable this transition. But that is a hypothetical transition that bets on young people making technologically relevant choices a long time from now. How is Web3 relevant for the workforce today?

Digital forms of identity have already become a fixture in the hiring process. Candidates applying for jobs are expected to have a verifiable digital presence. A strong presence on platforms like Twitter, Linkedin or Instagram can translate to meaningful wage premiums. But these forms of identity lack transactional context.

While a person may be an “influencer” on Linkedin, it may not be so that they are good at the job. Even worse, they may not have done anything related to the position in years. The historical argument for blockchains in the context has been credentialing. Putting certificates on a blockchain can help accelerate verifying if a candidate is truly who they say they are. But the missing component truly is context.

There’s a reason why I believe so. Bringing traditional universities to issue their certificates on-chain is a large-scale coordination game involving organisations that rarely change their ways. The value of any ‘certificate-on-the-blockchain” venture is directly proportional to the number of universities that sign up for the network.

And each university may have its own incubated venture or standard they would like to see coming of scale. This means no single venture will have sufficient partner universities on board to be of relevance to potential employers. But it is a very different story if you consider contextual data around on-chain interactions.

What blockchains will enable are ‘fluid identity states” that are pseudonymous. Traditionally, the relationship between an employee and employer was considered monogamous. Since the industrial age, we presume individuals would allocate all eight workday hours to a single firm.

Surely this had its advantage in that employees were “protected” from market volatility and could anticipate fairly stable jobs. In regions like India, being employed by the government comes with status because of the stability and influence the job brings. But the arrival of the internet has changed the equation quite a bit.

Suddenly there is an exponential shift in the amount of leverage an individual has. For instance, when I write these words and leave them on a substack, I communicate with individuals from 90+ countries without necessarily being online all the time. (Substack recently released a reader insights page, and I was impressed to see that statistic. Weird flex, I know).

Tools like ChatGPT and Google give the average knowledge worker access to information that took days to sift through in a matter of seconds today. We collaborate remotely, at a global scale and take it for granted. Our predecessors waited for months to debate one another. We trash-talk each other on slack when not distracted by Twitter. But this gain in productivity has not translated to meaningful improvements in wages or opportunities for secure jobs. This is why we see trends like moonlighting and freelancing becoming a norm.

The idea that knowledge workers will wilfully bet their fates on a single firm comes to question even more when you consider the extent of layoffs we have seen in the recent past. There will be a repricing for tech-related jobs over the coming years because the stability it once offered no longer exists. Individuals will reconsider whether pursuing a job is as desirable as it once seemed.

Over the coming months, at least 5% of the labour force currently being laid off may pursue opportunities at startups or do their own thing. In many instances, firms may not need full-time commitment from employees joining them. For example, a seed-stage venture may need a designer only for 10 hours a month till they have a clear direction as to where they are heading. Similarly, a copywriter may be required only for a small fraction of the month.

Individuals will work for a limited period (low depth) with a wider variety of firms (high breadth). This “agency-fication” of the workforce has already been in force for quite some time. “Fluid identity States’ in this context refers to a person having different levels of engagement with a broad mix of firms, each doing very different things. For instance, a designer may work only for half a day in a given month with a startup working on enabling Web3 onboarding but ~100 hours with a different venture specialising in gaming.

On-chain platforms like Questbook and Gitcoin today make it possible for a third party to independently verify the extent of engagement and records of an individual’s interactions to verify if they are the professional they claim to be. You can see how the nature of a person’s engagement has evolved by checking how often and how much they were paid. As a result, on-chain transactions may be the richest “proof” of a person’s ability to do a job well.

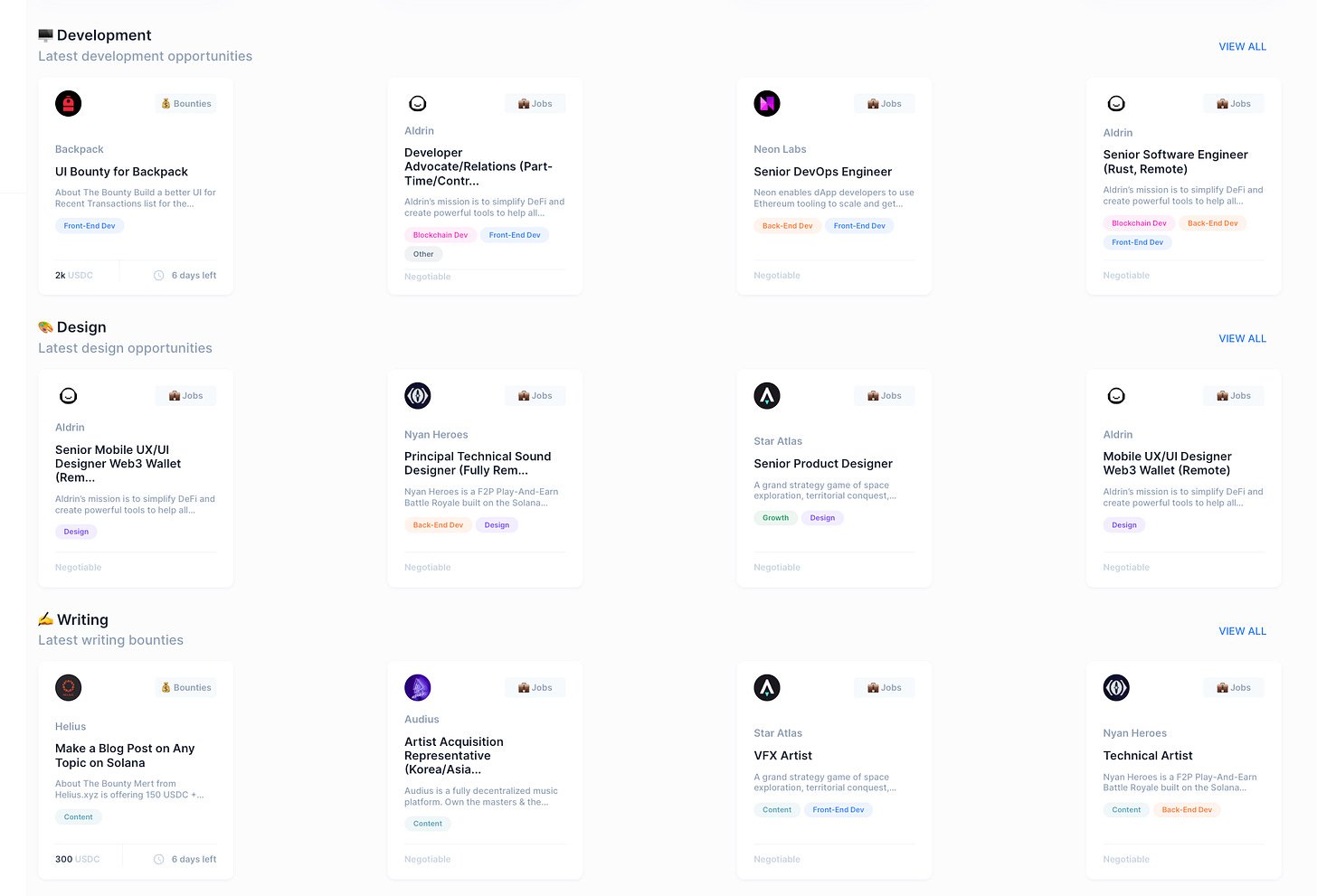

Communities like Superteam have taken this concept a step further. Part of how they measure their own “success” is in terms of community GDP – a rough measure of the amount of capital members have earned through short-term gigs. They have now released a platform to enable community members to discover, partake and earn through a series of opportunities. Close to a million dollars have been disbursed as grants as of October 2022. $13 million worth of opportunities is listed on SuperTeam Earn today. These platforms are effective gateways that allow new entrants to Web3 to seek jobs and build an identity around their wallet addresses.

It may seem far-fetched, but fluid state identities are already functioning today. For instance, when Optimism released its airdrop, it targeted multi-sig holders, DAO voters and Gitcoin grant donors. Tools like Degen Score issue soul-bound NFTs that track users’ interaction with DeFi platforms. These scores are then used to verify if a person is truly an expert in DeFi.

You can do much of this on Freelancer or Fiverr already. To a certain extent, it’s possible to understand how much a person has been paid and by whom. Platforms have every incentive to share accurate figures on this with prospective employers, as lost trust is bad for their business. You can also verify whether a person has had active engagements in the past by reading reviews too.

So we may be taking a hammer (blockchains) and searching for a nail here (like we almost always do). But in the case of Web2 platforms that exist today, the data is owned by the platform. It restricts commercial interactions between talent and firms looking to hire them. Composable identities may be an alternative approach to enabling more individuals to land better opportunities.

What do I mean by that? When an individual that has made a thousand trips on Uber leaves the platform, their data stays with Uber. The person doing the work has no mechanism to get their data out to a third party who could use it to appraise their value in the labour market. Free flow of employee data could lead to more efficient wage pricing if there were a way to verify, validate and evaluate the data.

Without a framework to share reputation or wage-related information, employees are at the mercy of the person conducting recruiting in any external firm to give them their due wages. But it does not have to be that way. There can be a transition of user data from platform dependency to protocol ownership. What does that look like?

Lens protocol defines itself as a “composable and decentralised” social graph. The crux of the concept is a user owns their network of friends and data on the protocol. They can then plug and play with their identities on various apps. A very crude, Web2 version of this would be – what if you could have your following on Twitter available on YouTube too? The idea is that people should not rely on a single platform and its owner (like Elon Musk) to get in touch with their friends. But what would this look like in the context of work?

Over time, work-specific social graphs would emerge on protocols like Lens. Much like we have GitHub for developers and Behance for designers, niche, job-specific applications will likely be used by users who own their data. Why does this matter? Because, for one, it reduces the risk that comes with de-platforming. If you make your income predominantly through Fiverr’s platform and they ban you, it translates to a loss of livelihood.

But if protocols like Lens were used to create freelancing platforms, a user could simply use another client and engage with the same list of users paying him earlier.

Protocols that enable users to own their data and social graphs are a good enough solution to platform monopolies that have emerged in the last few decades. It is hard to dethrone LinkedIn or Facebook today because leaving the platforms means having no way to get in touch with other users on these platforms. Deleting an account could translate to losing relationships built over time.

But in instances where users do own the social graph, they can switch to a different client to ping their friends. Deleting social media accounts today is akin to being banned from the mall. Switching clients interacting in protocols where users own the social graph is akin to changing restaurants because the one you are at is getting too noisy.

Naturally, people will not be transitioning over simply because they get a hedge from de-platforming risks. As we saw with NFTs and DeFi before, profit motives will initially be the key driver for a transition. Play to earn’s viral narrative compounded as more people recognised that they could make a living out of them. In hindsight, it did not sustain itself long enough.

But unlike games, social networks can retain and sustain larger user bases even when capital incentives decline. Why? Because network effects kick in as the user base itself grows. If I built an account on Lens with ±10,000 followers, I would continue to use the platform even if there were a decline in token-based rewards.

While owning one’s social graph and data is great, users also need primitives that help with coordination and capital. This is where DAOs fall into the equation. Multiple cooperatives run as on-chain, worker-led primitives today. According to data from Dune, over 200k multi-sig wallets are set up today through Gnosis.

The average month sees ±4000 multi-sig wallets being set up through them. Worker lead cooperatives could be more additive than employees working for corporations as these are loosely held organisations that don’t function until contributors can enrich themselves. People can take their labour elsewhere if they do not find a DAO working for their benefit.

When I first began working on this piece, I was working with the assumption that identity verification is the core value proposition blockchains can offer in the context of work. I then realised job listing platforms could also use them to build rich and contextual data sets around the commercial interactions a person has done from a wallet.

So I went down that rabbit hole, only to realise most of the time, workers barely own their data, and perhaps, tools like Lens Protocol can make a dent there. There’s a pattern I saw here. And that is, blockchains don’t upend work as we know it. They only provide infrastructure or tools to change how we work.

Tools like multi-sig wallets and DAOs can encourage more individuals towards entrepreneurship. Likewise, an ever-increasing number of people in remote economies may get paid higher wages due to the arrival of primitives like stablecoins. But at scale, much like the internet itself, blockchains will become mere infrastructure—tools hidden in the background.

Used by people who are blissfully unaware of the technical intricacies of their tools. There will be no “Web3 freelancer”. Or Web3 Linkedin. Whatever’s next will likely not mention these technological primitives but embed them in the user experience. The average person does not care about whether something is built on Arbitrum, Polygon or Solana as much as they care about how they can pay the bills.

There is much to be bullish about what Web3 can do – for ownership, entrepreneurship and global-scale collaboration. But it is just as important to recognise that the average person may never use all these tools. At least, not in the forms we use them today. The primitives we have today are somewhat similar to the SMTP protocol for email. There used to be a time when everyone maintained their email servers and clients. We almost entirely rely on Gmail to take care of things today.

What happens over the next decade will be an era of retail apps built with a focus on specific skill sets. Trends like globalisation and freelancing are here to stay. And the internet needs primitives that accelerate the pace at which we can hire. Blockchains fit well in that equation for now. However, it will be long before sufficient demand and liquidity for labour on these primitives.

A decade back, if someone said there would be a platform offering $5 gigs, it may have sounded stupid. And yet, a decade later, Fiverr is the go-to tool for most entrepreneurs launching something new on a bootstrapped budget. I guess that’s what blockchains also require – a decade’s worth of wait, and slow, compounding growth of users making a living from it. Be it in the form of NFT royalties, grinding in games or partaking in DAO cooperatives.

I will see you guys later this week with some work we have been doing on user-generated content and gaming. Have a pleasant week, and avoid getting liquidated in the market volatility.

Before these pieces go live, I discuss most things covered in the newsletter on our Telegram. We have been exploring the state of lay-offs and how music could be upended using NFTs lately. Consider joining us to connect with ~2500+ researchers, investors and operators.

Some of the smartest minds I know have published a 38-page report that goes through four years’ worth of Bitcoin volatility surface regimes. Make sure to take a look at it if derivatives interest you.