TL;DR – I try to explain the reasoning behind the rise of digital first marketplaces and why tokens induce entirely new behavioral patterns in market participants. We compare LooksRare’s massive short-term growth with OpenSea’s metrics and try to understand how the team hacked through growth and if it can be sustained.

Hey,

Imagine this: It is January 31, 2000. Just six months ago, two kids launched Napster in their garage, and before you knew it, everybody was downloading music on the web. Jeff Bezos is still some nerdy bald guy selling books on the internet (sorry, Jeff). Rumours of an internet bubble are spreading like wildfire. I was in kindergarten at the time, so I have no clue what had transpired. But I would presume the world was marvelling at what is possible on this new “information highway” much like we think about the possibilities of the blockchain today. In the following months in the year 2000, few would figure out the key difference that would lead to some companies losing billions in value and some generating trillions for their shareholders.

The founders of Napster were served their first lawsuit right around that time. The world of music was waking up to a new threat without necessarily realising how everything was about to change. You see, Napster crashed the unit economics of music. Before, every music track had to account for what share went to creating the CD, the distribution shop, the record label, and even the artist’s manager. The industry threat was clear: You had a platform that took intellectual property and made it easily accessible on a global scale by going digital. Although iTunes (and later on Spotify) eventually owned the music market, a similar trend was evident in education (e.g., Coursera, e-books), movies (e.g., Netflix, Apple Movies), gaming (e.g., Steam, Xbox Live), and even dating (e.g., Tinder, Bumble). Life went digital. Not solely because it was more convenient but because these platforms changed the unit economics, especially at larger scales.

Digital goods all of a sudden competed with physical goods. So, for example, the Twitter feed competed with print newspapers. But it was hard to do so because of a simple maxim. The unit cost of replicating a digital consumption good is a fraction of what it is for a physical counterpart. For example, an artist spends the same amount of effort making music regardless of whether it is streamed by 1000 people or 10,000. But the same cannot be said about physical CDs because there is added cost on each new CD manufactured. In most of web2, the infrastructure costs are carried by the platform itself as is the case with Instagram or YouTube. Platforms bear these costs as an investment of acquiring attention, which can then be commoditised, packaged and resold to advertisers. That was web2’s original innovation. Making a financial product out of human attention and selling it to the highest bidder.

In other words:

-

Creators like going digital as their ROI on time spent on producing content scales exponentially as their audience scales up; and

-

Platforms spend money on infrastructure (e.g., servers, censoring, distribution) as they can retain attention, which in turn brings in ad-dollars.

But why does all this matter?

Because 20 years on, there is a new digital primitive in the market that may be upending how we think of content all over again. You may have guessed it already: NFTs. In my view, NFTs represent another seismic shift for content. Markets have been quick to either dramatise NFTs as dumb JPGs or the holy grail for digital monetisation. I broke them down a little in my earlier piece on BAYC in July 2021. (Bored Apes rallied from $10k to $250k since I wrote about it, and no, I did not buy them.)

NFTs matter because of several reasons that the market may not be accounting for yet:

-

They collapsed the cost of intellectual property provenance exponentially. Historically, you could not verify if a source of art came from a specific source or see if a third party owned it without trusting an intermediary whose expertise could be faulty. While there are copyright infringement cases between the meatspace and the metaverse (see this, this, and this), it is safe to say that this use case has been empowering for digital creatives.

-

They collapsed the cost of proximity to celebrities or, in more technical terms – memetic proximity. Apparel from Gucci and Louis Vuitton cost money to acquire, maintain, and display. You may have to optimise for where they are displayed, too. In comparison, you can show an NFT in the same collection owned by Justin Bieber or Jay Z on Twitter without it being ultimately cringe. That is also more liquidity in blue-chip NFTs than Veblen goods like rare sneakers. ( I am writing a long form on how all of web3 is a game of memetics. Will share in weeks to come)

-

NFTs replace the middleman much like digital content did 20 years back. Except, in this case, instead of hoping for platforms to compensate them, they monetise directly from end consumers. Instead of a network of anonymous uploaders sharing files as was the case with Napster, the creators benefit directly from every transaction for said consumption goods. I don’t think they replace distribution with Spotify and Instagram’s platforms because there are no platforms with such scale. Still, they offer an entirely new way to monetise .

-

This is a bit controversial: NFTs have likely shifted how we think of intellectual property globally. Netflix came to India in 2016. Spotify? In 2019. This matters because India is the market that helped much of the web’s fastest-growing firms reach their first billion users. Part of the reason for this delay is the archaic legal structuring around DRM and licensing. In comparison, NFTs are accessible globally from day one. This may not be a trend that will stick around forever, but for now, it is the case.

All technologies in their early stages are typically accessed only by the ultra-rich. My favorite example of this is aluminum. In the mid-19th century, this metal was valued so highly that it was used in crown jewellery, and Napoleon had a set of cutlery made of it for guests. By the early 20th century, its cost collapsed to a point when the Wright brothers were using it for their plane’s engine. A more recent yet similar example is that of mobile devices. Between the early 2000s and now, the cost of mobile phones has fallen exponentially if you consider the unit cost of computing power in them. A similar variation is visible with NFTs today. You either have the extreme high-end of the market (e.g., Cryptopunks, BAYC) or spammy 10K NFT collections released with free access. The fact that they are liquid means they are being traded, and the price is part of what attracts users to them – for now. But in my opinion, the subsequent billion users may not use NFTs as speculatory instruments.

The Difference Embedded Markets Make

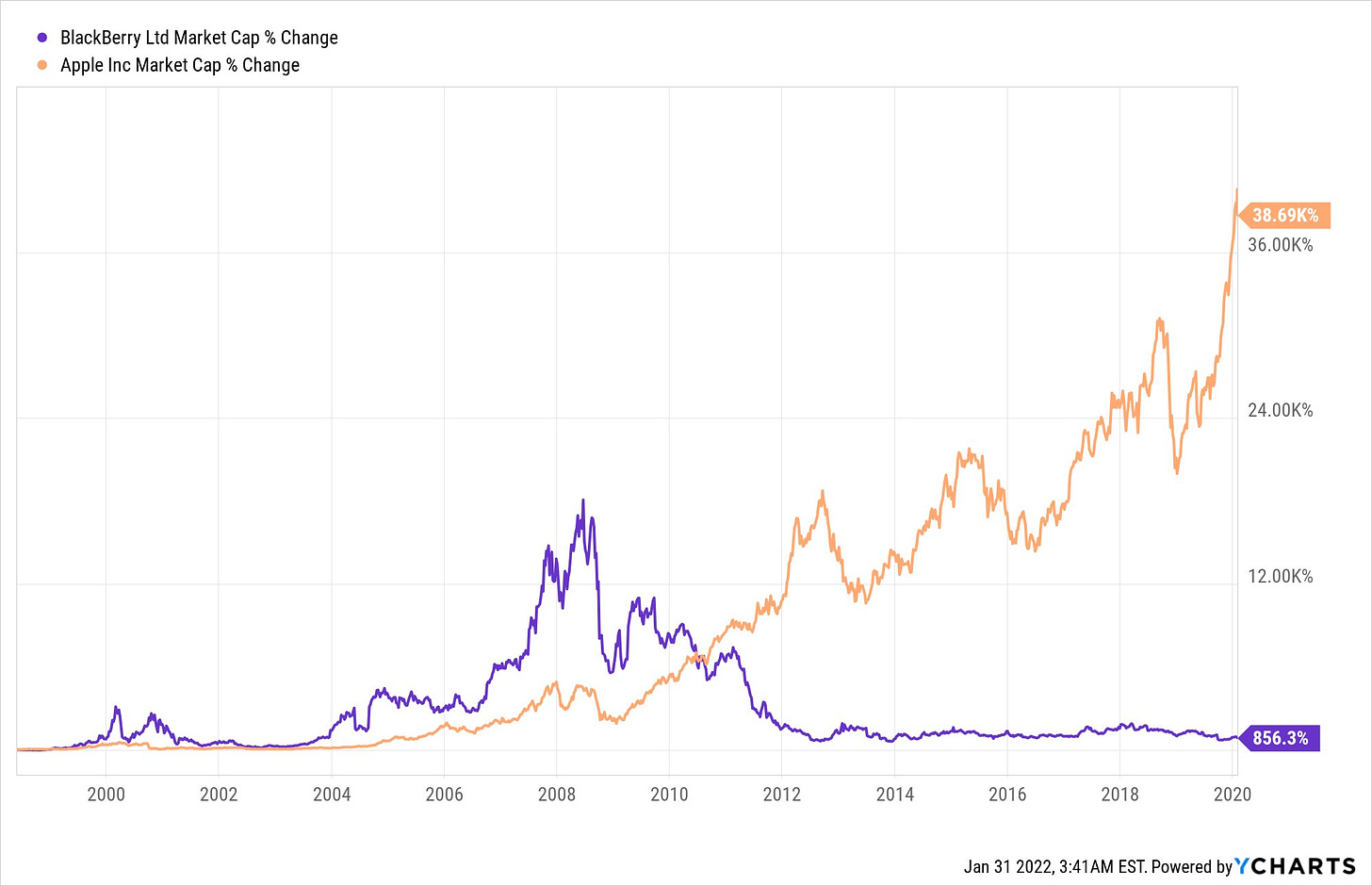

I need to stop bashing Blackberry for all of my examples but consider the chart above. It shows the percentage change in the value of Apple’s and Blackberry’s stocks since the early 2000s. Part of what makes Apple such a profitable enterprise is its deeply embedded product stack. A user engaging with one Apple product generates revenue for Apple from the moment they buy the hardware and every time they subscribe to apps in the Apple ecosystem. Blackberry, in comparison, used to make money only when their hardware was sold. This trend of selling hardware at diminished prices in exchange for generating revenue from recurring revenue is common for consoles today, too. You don’t just buy an Xbox anymore. Instead, you purchase an Xbox Live Gold membership which lets you play online and access an extensive library of games. You don’t just buy a fridge… never mind, we are not there yet with food.

But to get back to my point – Digital markets are attractive for businesses because:

-

They reduce geographic barriers on the frequency of a transaction occurring;

-

They enable strong, sticky communities that are financially invested in coming back to the product, which is likely why Twitter and LinkedIn have paid subscriptions now; and

-

The network effects are strong, and the cost of servicing each new user declines as the platform scales.

With all of this in context, it may serve well to ask a few questions:

-

Do web2 (aka Web 2.0) platforms have economic reasons to embed NFTs in their operations?

-

How do web3 (aka Web 3.0) native platforms compare against one another when tokenised or non-tokenised?

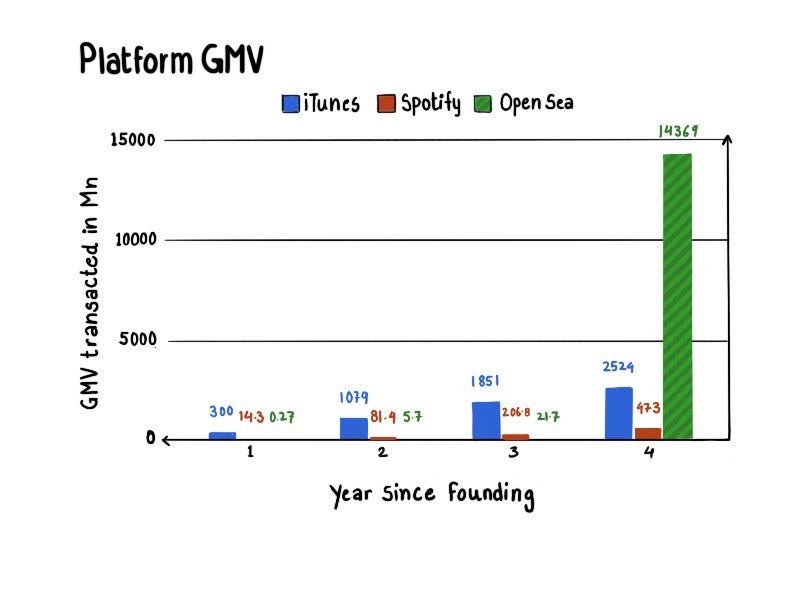

To answer the first question, we need to first look at traditional centralized platforms like Spotify and iTunes and compare them to the new peer-to-peer NFT marketplace OpenSea. Because OpenSea is a privately held corporation, we are limited in the amount of public and reliable data available. So, for the moment, let’s go with Gross Merchandise Volume (GMV) as a base metric to compare these platforms. Gross merchandise volume is the total dollar volume of merchandise transacting through the marketplace in a specific period. For a relatively simple comparison, we take the first four years of GMV growth for iTunes (2004-2008), Spotify (2009-2013), and OpenSea (2018-21). These are not entirely fair comparisons; each of these markets has different characteristics. Obviously, iTunes sells and rents out tracks, while Spotify has always had a subscription model, and OpenSea sells stand-alone NFTs. So, it is fair to assume that profitability will vary widely; but we are only trying to see how these new digital platforms took off compared to one another here.

That uptick in OpenSea’s GMV is what every enterprise, fashion-label, tech-bro, artist and financier has been obsessing about since at least mid-last year. Digital native consumption goods like NFTs unlock entirely new user behaviours and business models.

But, first, on the user-behaviour front:

-

We are witnessing the gamification of digital asset consumption. Historically you had no upside in renting a movie or streaming music. Web3 models allow communities to form around enabling creatives to make an asset (piece) and derive revenue from it. It is far-fetched to believe community ownership of digital consumption goods is possible just yet because its infrastructure does not exist

-

The rapid financialisation of digital asset goods means platforms earn more on transactions on the platform. Web2 financialised consumer attention and sold it to advertisers. Web3 transferred that ability to creators and their audience. Historically, this was something only games could do. They could create an in-game asset (out of thin air), sell it to a user and earn on platform royalties when gamers sold it between one another. Now anyone can do it. It is the closest a citizen would come to literally minting money legally.

These may seem like numbers taken out of thin air, but consider the following chart.

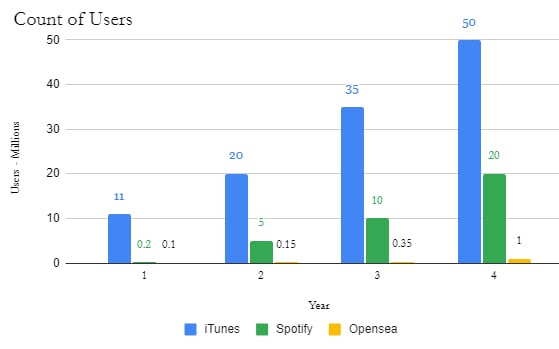

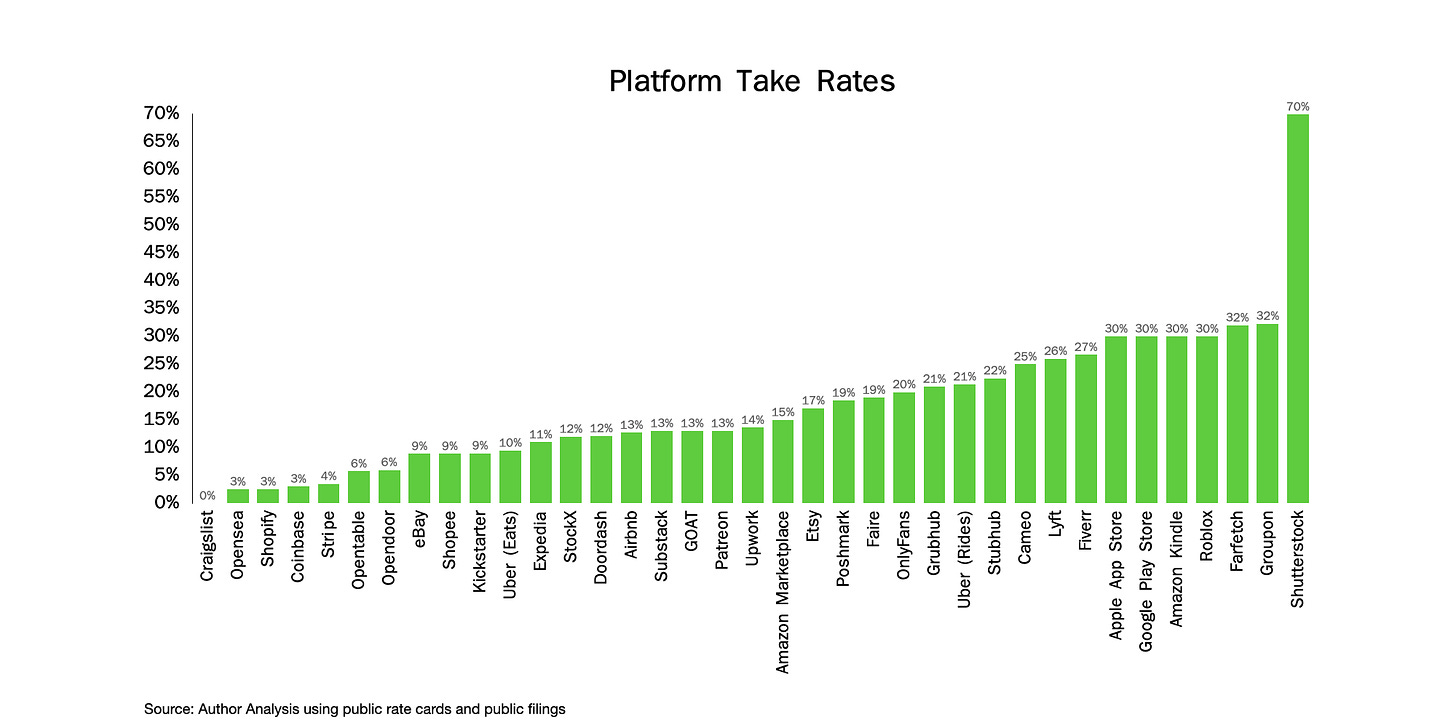

Platform revenue is the amount of money a platform makes from its gross merchandise value. Platforms that see transactions occurring less frequently have high take rates, while those with extremely high frequency have a far lower take rate. Marketplaces for digital consumption goods are attractive because they come at the intersection of high frequency, high volume and low operational costs. Consider Stripe, for example. The 4% they charge has to account for insuring fraud across every transaction conducted through them, fees for banking partners on their network and transaction fees for sending money to merchants. It may seem like a lot, but it is not much if you consider the operational risks. Meanwhile, Lyft makes 25% on every journey. But if your network of drivers engages in a series of crimes, your ability to operate diminishes. The variables outside of your control are too high. Apple and Google Play get away with charging 30% because they have spent a decade building out hardware distribution through their phones and securing the operating system itself to a point where users trust them. In comparison, thin layer platforms like OpenSea barely have to worry about the operational costs of “producing” NFTs. Similar to web2 social networks like YouTube and Instagram, their core cost is in acquiring new users. This is part of the reason why platforms like Zora and OpenSea have spent millions on on-boarding non-crypto native users to their platforms. Naturally, this difference in unit economics extends to platform revenue, too. For context, consider the number of users on them after a few years of launching.

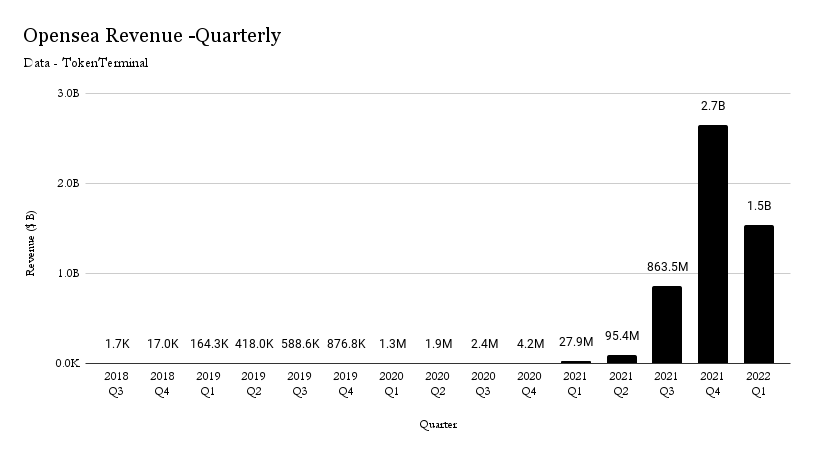

iTunes had a far stronger distribution than Spotify or OpenSea at launch because of Apple’s distribution. But compare it with the GMV figures shared above, and you will see why NFT-based digital marketplaces are valued the way they are. Last year, OpenSea did some $14.3 billion in volume with just one million users. The average amount traded per user comes to around $14,000 (which includes a lot of six-figure transactions). In comparison, the average price for the sale of a track when iTunes launched was $0.99, and that of Spotify was around $10 if you exclude ads. In other words, NFT marketplaces are laying the foundation for a new era of digital consumables that have far more profitability than existing ones like music or video subscriptions. The margin on these platforms will be a multiple of what traditional media have seen, which is why we see an influx of venture capital dollars towards them. Don’t take my word for it. Consider the chart below from TokenTerminal as proof. Open sea did ~3.5 billion in revenue (across royalty plus platform fee) last year. Half of that sum is already done in a single month this year. So much for a bear market.

The Emergence Of Tokenised Marketplaces

For all the benefits of ownership, unit economics, and revenue multiples NFT based marketplaces offer: They have one key trait that should alarm almost anyone investing in them. NFT data being query-able at the blockchain level means an individual can list the same asset on multiple platforms. Unlike digital goods (like Spotify or iTunes), the IP rights for listed assets are not owned by the platform but rather by the user. This means a creator can take their assets and list it elsewhere. The lack of lock-in makes most NFT based marketplaces vulnerable in that users can start conducting transactions elsewhere. We saw this happen quite recently with the NFT marketplaces LooksRare and OpenSea. The venture began with an airdrop aimed at individuals that had traded a specific volume of ETH in NFTs. Users were required to list an NFT on Looksrare to claim their drops. The result? Some 3,000 users use LooksRare each day within a matter of days, with about 10,000 new users coming to the platform every day, according to data from Nansen. The following two charts summarise the key difference between the platforms.

You see, while the count of transactions on Looksrare remains distinctly lower than that of OpenSea’s, the volume has often been considerably higher than that of OpenSea’s. In case you are wondering, yes, users are incentivised to wash-trade on the platform currently. The incentive model distributes ~$12 million in Looks token each users across traders on the platform. You could argue that this is an incredibly high cost for user acquisition, and I would nod my head to that. But here’s the kicker: Each of these traders are required to pay 2% to the platform and anywhere between 5% to 10% in royalty to the artist. Effectively, wash traders are doing on the platform to acquire assets at a discount to the spot market. If platform fee + royalty paid is higher than the price of the tokens rewarded, users will have no incentive to continue trading on the platform. You may think that is dumb, but LooksRare has done ~$11 billion in volume and $220 million in revenue with a fraction of the users OpenSea currently has.

The natural question for anyone is whether the LooksRare model can sustain once the incentives stop. In my opinion, the real genius behind LooksRare token is not their air-drop or game-theoretical design of user behaviour in their marketplace. What is unique about them is how their strategy is structured. The $looks token that has been air-dropped gets individuals the right to a portion of the fees generated on the platform each day. Users choosing to hold the looks token they receive as part of the trading incentives on the product can receive a portion of the platform fees in perpetuity if they decide to stake it. The platform has effectively made a system where token holders get cash flow from the product they use. A web2 equivalent for this would be using AirBnB for five years only to realise you own enough ownership in the network for your dividends to cover rent. Such kind of ownership can unravel entirely different user behaviour. And that is the promise of web3.

In my opinion, NFTs will permanently change user behaviour in three significant ways:

-

Users will embrace their newborn power to move assets when they wish. Or even better: If digital goods gain cross-platform compatibility, to be able to list, trade, sell, and buy assets on multiple platforms at the same time;

-

By giving users ownership of the platform in the form of tokens, they will now have the rights to cashflow on the platforms they use in the same way that the NFT marketplace LooksRare pioneered; and

-

Through eradicating the need for posting low-value clickbait engagement, new content will be optimised for reach in the ad-driven web2 ecosystem.

The types of businesses that NFTs could already enable are barely scratching the surface. For example, major fashion houses like Louis Vuitton and Gucci, with billion-dollar revenues, have already been making great strides in the ecosystem. Meanwhile, Facebook seems to have dropped its focus on launching a stablecoin to focus on Meta, their attempt at the metaverse. And while musicians, athletes, and artists have embraced the asset class, some vocal concerns of fraud and “burning down forests” remain part of the conversation on NFTs.

The next few years will remind many of us of the early 2000s. We are still looking at the Sean Parkers of this era, tinkering on the edge of what will be possible. A potential boom and bust cycle is around the corner. This new digital instrument’s iTunes’ and Netflix’ are barely here. And we are all wondering how NFTs will become mass consumption goods. I am not a betting man but there are a few things I would be willing to bet on. Firstly, I expect NFTs to collapse in price to become an experience good instead of a speculatory asset within the next six months. There is no logic in limited count instruments released on a handful of people with an information edge spending their days looking at screens. Secondly, I expect the media and the NFT ecosystem to become more embedded. Access NFTs will be used to coordinate communities, as tickets for crowd-sourced events, and hold the rights to the work of a known artist. And finally, I expect that a general-purpose marketplace (like OpenSea) will face immense competition from stand-alone NFT storefronts, similar to how Amazon sees fierce opposition from Shopify stores. Currently, discovery of NFTs happen on markets and social media. It will soon occur in more intimate settings like a personal blog or chats.

One thing is certain: These are exciting times ahead of us. See you tomorrow.

Make sure to join us on Telegram if you enjoyed reading this piece.

P.s –

1. Thin money layers like those built by LooksRare are a core focus area for LedgerPrime, the organisation I work with. Of the ~55 investments we have made about 35+ are focused on just that. You can read this piece I wrote in 2020 for more context. Do write to me at joel@decentralised.co if you are building along these themes at the early stages.

2. We have the AMA with Aditya from Derivadex later today. You can RSVP for it here.

3. This article was co-authored with Sumanth Neppalli. Give him a follow here.

Joel

_________________________________________________________

I couldn’t be more excited to tell you this publication has its first official sponsor.

This piece was made possible with a sponsorship from Nansen. The platform saves analysts and traders hundreds of hours each month by allowing them to grab network level data with a simple click. No APIs, no going through network scanners or pulling contract addresses. Nansen visualises network level data on user behavior & transactions in a fraction of the time their peers do. Get started with a trial here or simply play with their dashboards here.

_________________________________________________________